Good Strategy, Bad Strategy

Does your strategy process produce strategic insight or is it a box ticking exercise?

Introduction

During my career, I have been involved in strategy from a wide range of perspectives, as a manager writing strategies, as a strategy consultant advising companies, as a mentor advising individuals and as an employee stuck at the sharp end of strategic decisions e.g. being made redundant as my business unit was sold off.

I’ve seen all sorts of ‘strategies’ from one liners that said it all to pretty bound folders that were left forlornly on the shelf until the next year. Much discussion in current times is whether strategic planning has any use at all, based on the idea that the world is changing so fast that it isn’t worth the effort. I don’t think this is the right approach and neither will key stakeholders, investors or shareholders.

So I thought today I’d take it back to basics and discuss the elements of what a good strategy is supposed to do and therefore whether what we are actually doing through strategic planning is adding value.

What Is Strategy?

Depending on our experience, we all come to the table with different ideas and expectations of what a strategy is and how it is developed. So let’s try to agree on what a strategy is and its purpose. The best definition I’ve come across is this one.

A strategy is the pattern or plan that integrates an organisation’s major goals, policies and action sequences into a cohesive whole. A well-formulated strategy helps to marshal and allocate an organisation’s resources into a unique and viable posture based on its internal competencies and shortcomings, anticipated changes in the environment and contingent moves by intelligent opponents.

James Brian Quinn from ‘The Strategy Process’ - Mintzberg, Quinn, Ghoshal (Italics - his emphasis, Bold - my emphasis)

Why is it good? Well, it gets to the heart of what strategy is and works for any size of company or market. It enables us to think about strategy as a guiding purpose and direction to where we want to go, but also in the way that we behave as an organisation e.g. purpose and sustainability. Let’s start in the middle.

‘A unique and viable posture’ is the Holy Grail of strategy - we are able to differentiate ourselves as an organisation uniquely. This is strategic insight; a truth that enables us to bring a specific solution or set of capabilities through the entirety of our resources - people, processes, finance etc - to the markets we serve in a deliberate way to create genuine competitive advantage.

Apple’s strategy is around product (and increasingly service) differentiation around the basis of simple, yet attractive design and advanced functionality and it will be an early (if not always first) mover. That simplicity extends to creating an Apple ecosystem where products work seamlessly together and design / advanced functionality runs through the entire marketing and sales experience e.g. the Apple Keynotes. This results in a greater profit margin per item and a greater total spend.

If we have this unique and viable posture, then it feeds back into a plan or pattern that brings together the major goals, policies and action sequences (programmes and projects) that direct the activities of the organisation into a coherent set of things. The programmes and projects have a clear purpose vs the major goals and the major goals support the strategy.

The strategy acts as a communications tool and a reference point for decision making. Policies which support decision making have clarity, reduce internal friction and make for quicker decision making. It’s much easier to talk about brand purpose, marketing, recruitment etc if it’s absolutely clear where you’re heading.

Many companies produce a wealth of plans and budgets with little or no strategic input from the senior team. That’s really just a budgeting exercise. It is strategic insight that should drive strategic planning, goal setting and programmes, not the other way round.

How Do We Get To Strategic Insight?

Strategic insight comes from a genuine (dare I say ruthless?) analysis of both internal competencies and the external marketplace both within the planning window and crucially beyond. Established organisations tend to take last year's figures and extrapolate without giving enough deep thought to environmental and technological changes, legislation etc. If you look at the performance of huge multinationals, you can see that past performance is not a predictor of future performance over a decade or so.

In one business unit strategy I wrote, the whole business was due to be affected by the introduction of new technology in the end user market. Guessing when that would seriously eat into sales was open to debate. However the forecast I was told to submit had the usual increasing revenue for a five year period!

Organisations tend to be even worse at assessing internal competencies. The idea that the people you hired or work with aren’t really up to the job or are incapable of delivering your big hairy goals might be a reality but it’s not one that many are happy to openly discuss or put into a strategy document. These problems can be even greater in a startup business where founders and early employees simply lack the leadership skills required to take a company from one level to the next.

If you’ve ever wondered why large organisations bring in management consultants, then look no further. It’s far easier for an external organisation to make a more analytical analysis of a company’s capability and the external environment and make deeply unpopular recommendations.If strategic decisions have implications stretched to billions, a few million on consultancy fees is neither here nor there. We might cover how consultancies work in a future post.

Developing A Strategic Process

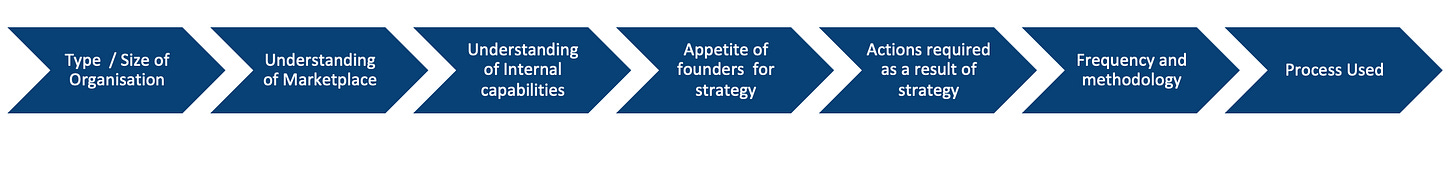

For those not blessed with that type of budget, what then? There are countless consultants and/or methodologies on the market. There’s no right or wrong answer but ultimately it boils down to a number of key considerations (Figure 1)

Figure 1: Considerations in Developing a Strategic Process

The size of the company and the market they serve matters. As companies grow in size and complexity, their ability to ‘pivot’ i.e. change strategy to make a significant change of operations becomes less. Two start-up founders in a co-working space can change direction in an afternoon. As they add staff, technical infrastructure, offices etc and go through rounds of funding, it becomes more painful to make change (the ‘Sunk Cost Fallacy’ also can hold true, of course). Typically, strategy here is a combination of informal analysis, reflection, and emerging as a result of increased market knowledge, with strategic changes communicated and actioned quickly.

As companies start to get beyond about 30 employees, then the strategy needs to be more explicitly communicated. Employees have less access to the founding members so assumptions around strategy can start to become problematic with people putting on their own spin.

At higher numbers, strategy begins to become mixed with financial and budgetary planning and the planning horizon extends.At the top end, large multinationals are effectively supertankers taking 3-5 years to make a major turn, organisations like the UK National Health Service 10 years. Reviewing the strategy once a month makes little sense, although scanning the horizon for new developments in the market should be frequent.

An agile strategy type approach may be entirely suitable for a startup or new business unit where there is little market information but inappropriate for a well established organisation in a mature market. A simple SWOT analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) may be appropriate if there’s a genuine openness to the discussion. However, if the leadership team is not open to using a particular methodology or to discussing strategy at all then any strategy workshop can be a long and painful day!

The key, whatever periodicity or methodology is chosen, is that organisations make a conscious effort to think openly and honestly about internal capabilities and the external market, come to a strategy and embed it effectively through the organisation.

Summary

Strategy and a strategic process are highly contextual. Finding something that works and that people want to participate in is more valuable than imposing a methodology. However ultimately, organisations need to find something. Stakeholders and investors demand it.

Whatever you choose, answer the following two questions based around the definition of strategy.

Does your strategy have a unique and viable posture based on its internal competencies and shortcomings, anticipated changes in the environment and contingent moves by intelligent opponents?

Does your strategy integrate your organisation’s major goals, policies and action sequences into a cohesive whole?

If the answer is yes to both, then you’re in a strong position. If there's hesitation, then it may be time to rethink and/or bring in some help.

Until Next Time

Pete